Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg testifies before Senate

Sen. Chuck Grassley: Committees on the Judiciary and Commerce, Science, and Transportation will come to order. We welcome everyone to today's hearing on Facebook's social media privacy and the use and and abuse of data. Although not unprecedented, this is a unique hearing. The issues we will consider range from data privacy and security to consumer protection and the Federal Trade Commission enforcement, touching on jurisdictions of these two committees. We have 44 members between our two committees, that may not seem like a large group by Facebook standards, but it is significant here for a hearing in the United States Senate. We will do our best to keep things moving efficiently given our circumstances. We will begin with opening statements from the chairman and ranking members of each committee starting with Chairman Thune and then proceed with Mr. Zuckerberg's opening statement. We will then move on to questioning. Each member will have five minutes to question witnesses. I'd like to remind the members of both committees that time limits will be, and must be, strictly enforced given the numbers that we have here today. If you're over time, Chairman Thune and I will make sure to let you know. There will not be a second round as well. Of course there will be the usual follow up written questions for the record. Questioning will alternate between majority and minority and between committees. We will proceed in order based on respective committee seniority. We will anticipate a couple of short breaks later in the afternoon. And so it's my pleasure to recognize the Chairman of the Commerce Committee, Chairman Thune, for his opening statement.

Sen. John Thune: Thank you Chairman Grassley. Today's hearing is extraordinary. It's extraordinary to hold a joint committee hearing. It's even more extraordinary to have a single CEO testify before nearly half of the United States Senate. But then Facebook is pretty extraordinary. More than 2 billion people use Facebook every month. 1.4 Billion people use it every day — more than the population of any country on earth except China and more than four times the population of the United States. It's also more than 1500 times the population of my home state of South Dakota. Plus, roughly 45% of American adults report getting at least some of their news from Facebook. In many respects, Facebook's incredible reach is why we're here today. We're here because of what you, Mr. Zuckerberg, have described as a breach of trust. A quiz app used by approximately 300,000 people led to information about 87 million Facebook users being obtained by the company, Cambridge Analytica. There are plenty of questions about the behavior of Cambridge Analytica and we expect to hold a future hearing on Cambridge and similar firms. But as you said, this is not likely to be an isolated incident — a fact demonstrated by Facebook's suspension of another firm just this past weekend. You've promised that when Facebook discovers other apps that had access to large amounts of user data, you will be ban them and tell those affected. And that's appropriate. But it's unlikely to be enough for the two billion Facebook users. One reason that so many people are worried about this incident is what it says about how Facebook works.

The idea, that for every person who decided to try an app, information about nearly 300 other people was scraped from your services, to put it mildly, disturbing. And the fact that those 87 million people may have technically consented to making their data available doesn't make most people feel any better. The recent revelation that malicious actors were able to utilize Facebook's default privacy settings to match email addresses and phone numbers found on the so-called Dark Web to public Facebook profiles, potentially affecting all Facebook users, only adds fuel to the fire. What binds these two incidents is that they don't appear to be caused by the kind of negligence that allows typical data breaches to happen. Instead they both appear to be the result of people exploiting the very tools that you've created to manipulate users' information. I know Facebook has taken several steps and intends to take more to address these issues. Nevertheless, some have warned that the actions Facebook is taking to ensure that third parties don't obtain data from unsuspecting users, while necessary, will actually serve to enhance Facebook's own ability to market such data exclusively. Most of us understand that whether you're using Facebook, or Google, or some other online services, we are trading certain information about ourselves for free or low-cost services. But for this model to persist, both sides of the bargain need to know the stakes that are involved. Right now I'm not convinced that Facebook's users have the information that they need to make meaningful choices. In the past, many of my colleagues on both sides of the aisle have been willing to defer to tech companies efforts to regulate themselves. But this may be changing.

Just last month, in overwhelming bipartisan fashion, Congress voted to make it easier for prosecutors and victims to go after web sites that knowingly facilitate sex trafficking. This should be a wakeup call for the tech community. We want to hear more, without delay, about what Facebook and other companies plan to do to take greater responsibility for what happens on their platforms. How will you protect users data? How will you inform users about the changes that you are making? And how do you intend to proactively stop harmful conduct instead of being forced to respond to it months or years later? Mr. Zuckerberg, in many ways, you and the company that you created — the story that you've created — represent the American dream. Many are incredibly inspired by what you've done. At the same time, you have an obligation and it's up to you to ensure that that dream doesn't become a privacy nightmare for the scores of people who use Facebook. This hearing is an opportunity to speak to those who believe in Facebook and to those who are deeply skeptical about it. We are listening, America's listening, and quite possibly the world is listening, too.

Sen. Chuck Grassley: Thank you, now ranking member Feinstein.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein: Thank you very much Mr. Chairman, Chairman Grassley, Chairman Thune, thank you both for holding this hearing. Mr. Zuckerberg thank you for being here. You have a real opportunity this afternoon to lead the industry and demonstrate a meaningful commitment to protecting individual privacy. We have learned over the past few months, and we've learned a great deal that's alarming. We've seen how foreign actors are abusing social media platforms like Facebook to interfere in elections and take millions of Americans' personal information without their knowledge in order to manipulate public opinion and target individual voters.

Specifically, on February 16, Special Counsel Muller issued an indictment against the Russia-based Internet Research Agency and 13 of its employees for interfering operations targeting the United States. Through this 37-page indictment, we learned that the IRA ran a coordinated campaign through 470 Facebook accounts and pages. The campaign included ads and false information to create discord and harm Secretary Clinton's campaign and the content was seen by an estimated 157 million Americans. A month later, on March 17, news broke that Cambridge Analytica exploited the personal information of approximately 50 million Facebook users without their knowledge or permission. And last week we learned that number was even higher. 87 million Facebook users who had their private information taken without their consent. Specifically, using a quiz he created, Professor Kogan collected the personal information of 300,000 Facebook users and then collected data on millions of their friends. It appears the information collected included everything these individuals had on their Facebook pages. And according to some reports, even included private direct messages between users. Professor Kogan is said to have taken data from over 70 million Americans. It has also been reported that he sold this data to Cambridge Analytica for eight hundred thousand dollars. Cambridge Analytica then took this data and created a psychological welfare tool to influence United States elections. In fact the CEO, Alexander Nix, declared that Cambridge Analytica ran all the digital campaign, the television campaign, and its data informed all the strategy for the Trump campaign. The reporting has also speculated that Cambridge Analytica worked with the Internet Research Agency to help Russia identify which American voters to target with its propaganda.

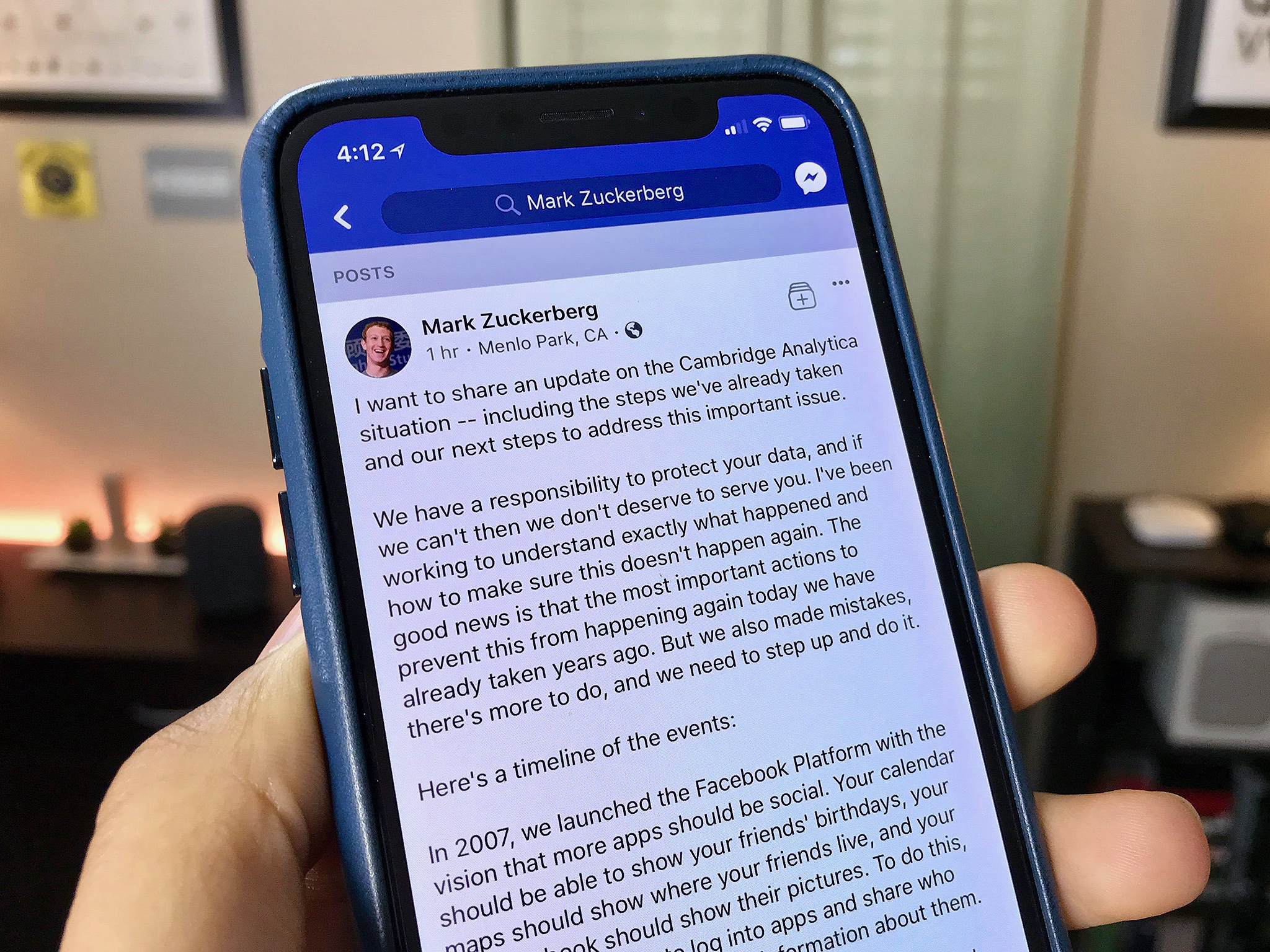

Master your iPhone in minutes

iMore offers spot-on advice and guidance from our team of experts, with decades of Apple device experience to lean on. Learn more with iMore!

I'm concerned that press reports indicate Facebook learned about this breach in 2015, but appears not to have taken significant steps to address it until this year. So this hearing is important and I appreciate the conversation we had yesterday and I believe that Facebook, through your presence here today and the words you're about to tell us, will indicate how strongly your industry will regulate and or reform the platforms that they control. I believe this is extraordinarily important. You lead a big company with 27,000 employees and we very much look forward to your comments. Thank you Mr. Chairman.

Sen. Chuck Grassley: Thank you Senator Feinstein. The history and growth of Facebook mirrors that of many of our technological giants. Founded by Mr. Zuckerberg in 2004, Facebook has exploded over the past 14 years. Facebook currently has over 2 billion monthly active users across the world, over 25,000 employees, and offices in 13 U.S. cities and various other countries. Like their expanding user base, the data collected on Facebook users has also skyrocketed. They have moved on from schools, likes, and relationships statuses. Today, Facebook has access to dozens of data points, ranging from ads that you've clicked on, events you've attended, and your location based upon your mobile device. It is no secret that Facebook makes money off this data through advertising revenue, although many seem confused by, or are altogether unaware of this fact. Facebook generated 40 billion in revenue in 2017 with about 98% coming from advertising across Facebook and Instagram. Significant data collection is also occurring at Google, Twitter, Apple, and Amazon, and an ever-expanding portfolio of products and services offered by these companies grant endless opportunities to collect increasing amounts of information on their customers. As we get more free or extremely low-cost services, the tradeoff for the American consumer is to provide more personal data. The potential for further growth and innovation based on collection of data is unlimited. However, the potential for abuse is also significant. While the details of the Cambridge analytic situation are still coming to light, there was clearly a breach of consumer trust and the likely improper transfer of data. The Judiciary Committee will hold a separate hearing exploring Cambridge and other data privacy issues. More importantly, though, these events have ignited a larger discussion on consumers' expectations and the future of data privacy in our society.

It is exposed that consumers may not fully understand or appreciate the extent to which their data is collected, protected, transferred, used and misused. Data has been used in advertising and political campaigns for decades. The amount and type of data obtained, however, has seen a very dramatic change. Campaigns including Presidents Bush, Obama, and Trump all use these increasing amounts of data to focus on microtargeting and personalization over numerous social media platforms and especially Facebook. In fact, President Obama's campaign developed an app utilizing the same Facebook feature as Cambridge Analytica to capture the information of not just the app's users but millions of their friends. The digital director for that campaign, for 2012, described the data-scraping app as something that would, "wind up being the most groundbreaking piece of technology developed for this campaign." So the effectiveness of these social media tactics can be debated, but their use over the past years across the political spectrum and their increased significance cannot be ignored. Our policy towards data privacy and security must keep pace with these changes. Data privacy should be tethered to consumer needs and expectations. Now, at a minimum, consumers must have the transparency necessary to make an informed decision about whether to share their data and how it can be used. Consumers ought to have clearer information, not opaque policies and complex click-through consent pages. The tech industry has an obligation to respond to widespread and growing concerns over data privacy and security and to restore the public's trust. The status quo no longer works.

Moreover, Congress must determine if and how we need to strengthen privacy standards to ensure transparency and understanding for the billions of consumers who utilize these products. Senator Nelson.

Sen. Bill Nelson: Thank you Mr. Chairman. Mr. Zuckerberg, good afternoon. Let me just cut to the chase: If you and other social media companies do not get your act in order, none of us are going to have any privacy anymore. That's what we're facing. We're talking about personally identifiable information that, if not kept by the social media companies from theft, a value that we have in America being our personal privacy, we won't have it anymore. It's the advent of technology and of course all of us are part of it from the moment that we wake up in the morning until we go to bed. We're on those handheld tablets and online companies like Facebook are tracking our activities and collecting information. Facebook has a responsibility to protect this personal information. We had a good discussion yesterday. We went over all of this. You told me that the company had failed to do so. It's not the first time that Facebook has mishandled its users information. The FTC found that Facebook's privacy policies had deceived users in the past and in the present case we recognize that Cambridge Analytica … How can American consumers trust folks like your company to be caretakers of their most personal and identifiable information? And that's the question. Thank you.

Sen. Chuck Grassley: Thank you my colleagues and Senator Nelson. Our witness today is Mark Zuckerberg, founder, chairman, and chief executive officer of Facebook. Mr. Zuckerberg launched Facebook February, 4 2004 at the age of 19. And at that time he was a student at Harvard University. As I mentioned previously, his company now has over $40 billion of annual revenue and over 2 billion monthly active users. Mr. Zuckerberg, along with his wife, also established the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative to further philanthropic causes. I now turn to you. Welcome to the committee. And whatever your statement is, or if you have a longer one, it will be included in the record. So proceed, sir.

Mark Zuckerberg: Chairman Grassley, Chairman Thune, Ranking Member Feinstein, Ranking Member Nelson, and members of the committee, we face a number of important issues around privacy, safety, and democracy. And you will rightfully have some hard questions for me to answer. Before I talk about the steps we're taking to address them, I want to talk about how we got here. Facebook is an idealistic and optimistic company. For most of our existence. We focused on all the good that connecting people can do. And as Facebook has grown, people everywhere have gotten a powerful new tool for staying connected to the people they love, for making their voices heard, and for building communities and businesses. Just recently we've seen the #MeToo movement and the March for Our Lives organized, at least in part, on Facebook. After Hurricane Harvey, people came together to raise more than $20 million for relief. And more than 70 million small businesses use Facebook to create jobs and grow.

But it's clear now that we didn't do enough to prevent these tools from being used for harm as well. And that goes for fake news, for foreign interference in elections and hate speech, as well as developers and data privacy. We didn't take a broad enough view of our responsibility and that was a big mistake, and it was my mistake, and I'm sorry. I started Facebook, I run it, and I'm responsible for what happens here. So now we have to go through all of our relationships with people and make sure that we're taking a broad enough view of our responsibility. It's not enough to just connect people, we have to make sure that those connections are positive. It's not enough to just give people a voice, we need to make sure that people aren't using it to harm other people or to spread misinformation. And it's not enough to just give people control over their information, we need to make sure that the developers they share it with protect their information, too. Across the board, we have a responsibility to not just build tools, but to make sure that they're used for good. It will take some time to work through all the changes we need to make across the company, but I'm committed to getting this right. This includes the basic responsibility of protecting people's information, which we failed to do with Cambridge Analytica.

So here are a few things that we are doing to address this and to prevent it from happening again. First, we're getting to the bottom of exactly what Cambridge Analytica did and telling everyone affected. What we know now is that Cambridge Analytica improperly accessed some information about millions of Facebook members by buying it from an app developer. This was information that people generally share publicly on their Facebook pages like names, and their profile picture, and the pages they follow. When we first contacted Cambridge Analytica, they told us that they had deleted the data. About a month ago, we heard new reports that suggested that wasn't true. And now we're working with governments in the U.S., the U.K., and around the world to do a full audit of what they've done and to make sure they get rid of any data they may still have. Second, to make sure no other app developers out there are misusing data, we're now investigating every single app that had access to a large amount of information in the past. And if we find that someone improperly used data, we're going to ban them from Facebook and tell everyone affected. Third, to prevent this from ever happening again going forward, we're making sure that developers can't access as much information now. The good news here is that we already made big changes to our platform in 2014 that would have prevented this specific situation with Cambridge Analytica from occurring again today. But there is more to do and you can find more details on the steps we're taking in my written statement.

My top priority has always been our social mission of connecting people, building community, and bringing the world closer together. Advertisers and developers will never take priority over that as long as I'm running Facebook. I started Facebook when I was in college. We've come a long way since then. We now serve more than two billion people around the world and everyday people use our services to stay connected with the people that matter to them most. I believe deeply in what we're doing and I know that when we address these challenges we'll look back and view helping people connect and giving more people a voice as a positive force in the world. I realize the issues we're talking about today aren't just issues for Facebook in our community. There are issues and challenges for all of us as Americans. Thank you for having me here today and I'm ready to take your questions.

Sen. Chuck Grassley: I'll remind members that maybe weren't here when I had my open comments that we are operating under the five minute rule and that applies to those of us who are chairing the committee as well. Facebook handles extensive amounts of personal data for billions of users. A significant amount of that data is shared with third-party developers who you utilize your platform. As of early this year, you did not actively monitor whether that data was transferred by such developers to other parties. Moreover, your policies only prohibit transfers by developers to parties seeking to profit from such data. Number one, besides Professor Kogan's transfer, and now, potentially, CubeYou, do you know of any instances where user data was improperly transferred to third party in breach of Facebook's terms? If so, how many times has that happened and was Facebook only made aware of that transfer by some third party?

Mark Zuckerberg: Mr. Chairman thank you. As I mentioned, we're now conducting a full investigation into every single app that had access to a large amount of information, before we locked down platform to prevent developers from accessing this information around 2014. We believe that we're going to be investigating many apps, tens of thousands of apps, and if we find any suspicious activity, we're going to conduct a full audit of those apps to understand how they're using their data and if they're doing anything improper. And if we find that they're doing anything improper, we'll ban them from Facebook and we will tell everyone affected. As for past activity, I don't have all the examples of apps that we've banned here, but if you'd like, I can have my team follow up with you after this.

Sen. Chuck Grassley:Have you ever required an audit to ensure the deletion of improperly transfer data, and if so, how many times?

Mark Zuckerberg: Mr. Chairman, yes we have. I don't have the exact figure on how many times we have, but overall the way we've enforced our platform policies in the past is we have looked at patterns of how apps have used our APIs and accessed information as well as looked into reports that people have made to us about apps that might be doing sketchy things. Going forward, we're going to take a more proactive position on this and do much more regular spot checks and other reviews of apps, as well as increasing the amount of audits that we do. And again I can make sure that our team follows up with you on anything about the specific past stats that would be interesting.

Sen. Chuck Grassley: I was going to assume that sitting here today you have no idea. And if I'm wrong on that, you're telling me, I think, that you're able to supply those figures to us, at least as of this point.

Mark Zuckerberg: Mr. Chairman I will have my team follow up with you on what information we have.

Sen. Chuck Grassley: OK, but right now you have no certainty of whether or not— how much of that's going on, right? OK. Facebook collects massive amounts of data from consumers including content, networks, contact lists, device information, location, and information from third parties. Yet your data policy is only a few pages long. And provides consumers with only a few examples of what is collected and how it might be used. The examples given emphasize benign uses, such as connecting with friends, but your policy does not give any indication for more controversial issues of such data. My question: Why doesn't Facebook disclose to its users all the ways the data might be used by Facebook and other third parties and what is Facebook's responsibility to inform users about that information?

Mark Zuckerberg: Mr. Chairman, I believe it's important to tell people exactly how the information that they share on Facebook is going to be used. That's why every single time you go to share something on Facebook, whether it's a photo in Facebook, or a message in Messenger or WhatsApp, every single time there is a control right there about who you're going to be sharing it with, whether it's your friends, or public, or a specific group and you can change that or control that in line. To your broader point about the privacy policy, this gets into an issue that I think we and others in the tech industry have found challenging, which is that long privacy policies are very confusing. And if you make it long and spell out all the detail, then you're probably going to reduce the percentage of people who read it and make it accessible to them. So one of the things that that we've struggled with over time, is to make something that is as simple as possible so people can understand it as well as giving them controls in line in the product in the context of when they're trying to actually use them, taking into account that we don't expect that most people will want to go through and read a full legal document.

Sen. Chuck Grassley: Senator Nelson.

Sen. Bill Nelson: Thank you Mr. Chairman. Yesterday when we talked, I gave the relatively harmless example that I'm communicating with my friends on Facebook and indicate that I love a certain kind of chocolate. And all of a sudden I start receiving advertisements for chocolate. What if I don't want to receive those commercial advertisements. So your chief operating officer, Ms. Sandberg, suggested on the NBC Today show that Facebook users who do not want their personal information used for advertising might have to pay for that protection — pay for it. Are you actually considering having Facebook users pay for you not to use that information?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, people have a control over how their information is used in ads in the product today. So if you want to have an experience where your ads aren't targeted using all the information that we have available, you can turn off third party information. What we've found is that even though some people don't like ads, people really don't like ads that aren't relevant. And while there is some discomfort, for sure, with using information in making ads more relevant, the overwhelming feedback that we get from our community is that people would rather have us show relevant content there than not. So we offer this control that you're referencing. Some people use it. It's not the majority of people on Facebook. And I think that that's that's a good level of control to offer. I think what Cheryl was saying was that in order to not run ads at all, we would still need some sort of business model.

Sen. Bill Nelson: And that is your business model. So I take it that, and I use the harmless example of chocolate, but if it got into more personal thing communicating with friends and I want to cut it off, I'm going to have to pay you — in order not to send me using my personal information — something that I don't want. That, in essence, is what I understood Ms. Sandberg to say. Is that correct?

Mark Zuckerberg: Yes, Senator. Although, to be clear, we don't offer an option today for people to pay to not show ads. We think offering an ad-supported service is the most aligned with our mission of trying to help connect everyone in the world, because we want to offer a free service that everyone can afford.

Sen. Bill Nelson: OK.

Mark Zuckerberg: That's the only way that we can reach billions of people.

Sen. Bill Nelson: So, therefore, you consider my personally identifiable data the company's data, not my data, is that it?

Mark Zuckerberg: No, Senator. Actually at the first line of our Terms of Service say that you control and own the information and content that you put on Facebook.

Sen. Bill Nelson: Well, the recent scandal is obviously frustrating, not only because it affected 87 million, but because it seems to be part of a pattern of lax data practices by the company going back years. So back in 2011 it was a settlement with the FTC and now we discover yet another incidence where the data was failed to be protected. When you discovered the Cambridge Analytica that had fraudulently obtained all of this information, why didn't you inform those 87 million?

Mark Zuckerberg: When we learned, in 2015, that Cambridge Analytica had bought data from an app developer on Facebook that people had shared it with, we did take action. We took down the app and we demanded that both the app developer and Cambridge Analytica delete and stop using any data that they had. They told us that they did this. In retrospect, it was clearly a mistake to believe them and we should have followed up and done a full audit then. And that is not a mistake that we will make.

Sen. Bill Nelson: Yes, you did that and you apologize for it, but you didn't notify them. And do you think that you have an ethical obligation to notify 87 million Facebook users?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, when we heard back from Cambridge Analytica that they had told us that they weren't using the data and had deleted it, we considered it a closed case. In retrospect that was clearly a mistake. We shouldn't have taken their word for it and we've updated our policies and how we're going to operate the company to make sure that we don't make that mistake again.

Sen. Bill Nelson: Did anybody notify the FTC?

Mark Zuckerberg: No, Senator. For the same reason, that we'd considered it a closed case.

Sen. Chuck Grassley: Senator Thune.

Sen. John Thune: And Mr. Zuckerberg, would you do that differently today, presumably? That in response to Senator Nelson's question?

Mark Zuckerberg: Yes.

Sen. John Thune: … having to do it over. This may be your first appearance before Congress, but it's not the first time that Facebook has faced tough questions about its privacy policies. Wired magazine recently noted that you have a 14-year history of apologizing for ill-advised decisions regarding user privacy not unlike the one that you made just now in your opening statement. After more than a decade of promises to do better, how is today's apology different? And why should we trust Facebook to make the necessary changes to ensure user privacy and give people a clearer picture of your privacy policies?

Mark Zuckerberg: Thank you, Mr. Chairman. So we have made a lot of mistakes in running the company. I think it's pretty much impossible, I believe, to start a company in your dorm room and then grow it to be at the scale that we're at now without making some mistakes. And because our service is about helping people connect and information, those mistakes have been different and how we try not to make the same mistake multiple times. But in general a lot of the mistakes are around how people connect to each other just because of the nature of the service. Overall, I would say that we're going through a broader philosophical shift in how we approach our responsibility as a company. For the first 10 or 12 years of the company, I viewed our responsibility as primarily building tools that if we could put those tools in people's hands then that would empower people to do good things. What I think we've learned now, across a number of issues, not just data privacy but also fake news and foreign interference in elections, is that we need to take a more proactive role and a broader view of our responsibility. It's not enough to just build tools. We need to make sure that they're used for good. And that means that we need to now take a more active view in policing that ecosystem and in watching and, kind of, looking out and making sure that all of the members in our community are using these tools in a way that's going to be good and healthy. So, at the end of the day, this is going to be something where people will measure us by our results on this. It's not that I expect that anything I say here today to necessarily change people's view, but I'm committed to getting this right. And I believe that over the coming years, once we fully work all of these solutions through, people will see real real differences.

Sen. John Thune: Well and I'm glad that you all have gotten that message. As we discussed in my office yesterday, the line between legitimate political discourse and hate speech can sometimes be hard to identify and especially when relying on artificial intelligence and other technologies for the initial discovery. Can you discuss what steps that Facebook currently takes when making these evaluations, the challenges that you face, and any examples of where you may draw the line between what is and what is not hate speech?

Mark Zuckerberg: Yes. Mr. Chairman. I'll speak to hate speech and then I'll talk about enforcing our content policies more broadly. So, actually, maybe if you're OK with it, I'll go in the other order. So, from the beginning of the company in 2004 I started it in my dorm room, it was me and my roommate. We didn't have a technology that could look at the content that people were sharing, so we basically had to enforce our content policies reactively. People could share what they wanted and then if someone in the community found it to be offensive or against our policies, they'd flag it for us and we'd look at it reactively. Now increasingly, we are developing AI tools that can identify certain classes of bad activity proactively and flag it for our team at Facebook. By the end of this year, by the way, we're going to have more than 20,000 people working on security and content review, working across all these things. So when content gets flagged to us, we have those people look at it and if it violates our policies, then we take it down. Some problems lend themselves more easily to AI solutions than others. So hate speech is one of the hardest, because determining if something is hate speech is very linguistically nuanced. Right? You need to understand what is a slur and whether something is hateful — not just in English, but the majority of people on Facebook use it in languages that are different across the world. Contrast that, for example, with an area like finding terrorist propaganda, which we've actually been very successful at deploying AI tools on already. Today as we sit here, 99% of the ISIS and Al-Qaeda content that we take down on Facebook, our AI systems flag before any human sees it. So that's a success in terms of rolling out AI tools that can proactively police and enforce safety across the community. Hate speech, I am optimistic that over a five- to ten-year period we will have AI tools that can get into some of the nuances, the linguistic nuances, of different types of content to be more accurate in flagging things for our systems. But today we're just not there on that. So a lot of this is still reactive. People flag it to us, we have people look at it, we have policies to try to make it as not subjective as possible. But until we get it more automated, there is a higher error rate than I'm happy with.

Sen. Chuck Grassley: Senator Feinstein.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein: Thanks Mr. Chairman. Mr. Zuckerberg, what is Facebook doing to prevent foreign actors from interfering in US elections?

Mark Zuckerberg: Thank you. Senator. This is one of my top priorities in 2018 is to get this right. One of my greatest regrets in running the company is that we were slow in identifying the Russian information operations in 2016. We expected them to do a number of more traditional cyber attacks, which we did identify and notify the campaigns that they were trying to hack into them, but we were slow at identifying the type of new information operations.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein: When did you identify new operations?

Mark Zuckerberg: It was right around the time of the 2016 election itself. So since then, we — 2018 is an incredibly important year for elections, not just with the U.S. midterms, but around the world there are important elections in India, in Brazil, in Mexico, and Pakistan, and in Hungary that we want to make sure that we do everything we can to protect the integrity of those elections. Now, I have more confidence that we're going to get this right, because since the 2016 election, there have been several important elections around the world where we've had a better record. There's the French presidential election, there's the German election, there was the U.S. Senate. Alabama special election last year.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein: Explain what is better about the record.

Mark Zuckerberg: So we've deployed new AI tools that do a better job of identifying fake accounts that may be trying to interfere in elections or spread misinformation. And between those three elections, we were able to proactively remove tens of thousands of accounts before they could contribute significant harm. And the nature of these attacks, though, is that, you know, there are people in Russia whose job it is to try to exploit our systems and other internet systems and other systems as well. So this is an arms race. I mean, they're going to keep on getting better at this and we need to invest in keeping on getting better at this, too, which is why one of the things I mentioned before is we're going to have more than 20,000 people by the end of this year working on security and content review across the company.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein: Speak for a moment about automated bots that spread disinformation. What are you doing to punish those who exploit your platform in that regard?

Mark Zuckerberg: Well you're not allowed to have a fake account on Facebook. Your content has to be authentic. So we build technical tools to try to identify when people are creating fake accounts, especially large networks of fake accounts like the Russians have, in order to remove all of that content. After the 2016 election, our top priority was protecting the integrity of other elections around the world. But at the same time, we had a parallel effort to trace back to Russia the IRA activity, the Internet Research Agency activity, that was the part of the Russian government that did this activity in 2016. And just last week we were able to determine that a number of Russian media organizations that were sanctioned by the Russian regulator were operated and controlled by this Internet Research Agency. So we took the step last week, there was a pretty big step for us, of taking down sanctioned news organizations in Russia as part of an operation to remove 270 fake accounts and pages, part of their broader network in Russia that was actually not targeting international interference as much as ... I'm sorry let me correct that. It was primarily targeting spreading misinformation in Russia itself as well as certain Russian-speaking neighboring countries.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein: How many accounts of this type have you taken down?

Mark Zuckerberg: Across ... in the IRA specifically, the ones that we've pegged back to the IRA, we can identify the 470 in the American elections and the 270 that we specifically went after in Russia last week. There were many others that our systems catch which are more difficult to attribute specifically to Russian intelligence but the number would be in the tens of thousands of fake accounts that we remove. And I'm happy to have my team follow up with you on more information if that would be helpful.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein: Would you please? I think this is very important. If you knew in 2015 that Cambridge Analytica was using the information of Professor Kogan's, why didn't Facebook ban Cambridge in 2015? Why did you wait, in other words?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, that's a great question. Cambridge Analytica wasn't using our services in 2015 as far as we can tell. So this is clearly one of the questions that I asked our team as soon as I learned about this is, why did we wait until we found out about the reports last month to ban them? It's because as of the time that we learned about their activity in 2015, they weren't an advertiser, they weren't running pages, so we actually had nothing to ban.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein: Thank you. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Sen. Chuck Grassley: Thank you, Senator Feinstein. Now Senator Hatch.

Sen. Orrin Hatch: Well, this is the most intense public scrutiny I've seen for a tech-related hearing since the Microsoft hearing that I chaired back in the late 1990s. The recent stories about Cambridge Analytica and data mining on social media have raised serious concerns about consumer privacy. And naturally I know you understand that. At the same time, these stories touch from the very foundation of the internet economy and the way the websites that drive our internet economy make money. Some have professed themselves shocked — SHOCKED — that companies like Facebook and Google share user data with advertisers. Did any of these individuals ever stop to ask themselves why Facebook and Google don't charge for access? Nothing in life is free. Everything involves tradeoffs. If you want something without having to pay money for it, you're going to have to pay for it in some other way, it seems to me. And that's what we're seeing here. And these great Web sites that don't charge for access they extract value in some other way. And there's nothing wrong with that as long as they're upfront about what they're doing. In my mind, the issue here is transparency. It's consumer choice. The users understand what they're agreeing to when they access a website or agree to Terms of Service. Are websites upfront about how they extract value from users, or do they hide the ball? Do consumers have the information they need to make an informed choice regarding whether or not to visit a particular website? To my mind, these are questions that we should ask or be focusing on, Now, Mr. Zuckerberg, I remember well your first visit to Capitol Hill back in 2010. You spoke to the Senate Republican High Tech Task Force, which I chair. You said back then that Facebook would always be free. Is that still your objective?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, yes. There will always be a version of Facebook that is free. It is our mission to try to help connect everyone around the world and to bring the world closer together. In order to do that, we believe that we need to offer a service that everyone can afford and we're committed to doing that.

Sen. Orrin Hatch: Well if so, how do you sustain a business model in which users don't pay for your service?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, we run ads.

Sen. Orrin Hatch: I see. That's great. Whenever a controversy like this arises, there's always the danger that Congress's response will be to step in and overregulate. That's been the experience that I've had in my 42 years here. In your view, what sorts of legislative changes would help to solve the problems the Cambridge Analytica story has revealed? And what sorts of legislative changes would not help solve this issue?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, I think that there are a few categories of legislation that make sense to consider. Around privacy specifically, there are a few principles that I think it would be useful to discuss and potentially codify into law. One is around having a simple and practical set of ways that you explain what you're doing with data. And we talked a little bit earlier around the complexity of laying out this long privacy policy. It's hard to say that people fully understand something when it's only written out in a long legal document. This stuff needs to be implemented in a way where people can actually understand it — where consumers can can understand it — but that can also capture all the nuances of how these services work in a way that's not overly restrictive on providing the services. So that's one. The second is around giving people complete control. This is the most important principle for Facebook. Every piece of content that you share on Facebook you own and you have complete control over who sees it and how you share it and you can remove it at any time. That's why every day, about a hundred billion times a day, people come to one of our services and either post a photo or send a message to someone, because they know that they have that control and that who they say it's going to go to is going to be who sees the content. And I think that that control is something that's important that I think should apply to every service. And ...

Sen. Orrin Hatch: Go ahead.

Mark Zuckerberg: The third point is just around enabling innovation because some of these use cases are very sensitive like face recognition, for example. And I think that there's a balance that's extremely important to strike here where you obtain special consent for sensitive features like face recognition, but we still need to make it so that American companies can innovate in those areas or else we're going to fall behind Chinese competitors and others around the world who have different regimes for different new features like that.

Sen. Chuck Grassley: Senator Cantwell.

Sen. Maria Cantwell: Thank you Mr. Chairman. Welcome, Mr. Zuckerberg. Do you know who Palantir is?

Mark Zuckerberg: I do.

Sen. Maria Cantwell: Some people have referred to them as Stanford Analytica. Do you agree?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, I have not heard that.

Sen. Maria Cantwell: OK. Do you think Palantir taught Cambridge Analytica, as press reports are saying, how to do these tactics?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, I don't know.

Sen. Maria Cantwell: Do you think that Palantir has ever scraped data from Facebook?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, I'm not aware of that.

Sen. Maria Cantwell: Do you think that during the 2016 campaign, as Cambridge Analytica was providing support to the Trump campaign under project Alamo, were there any Facebook people involved in that sharing of technique and information?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator. We provided support to the Trump campaign similar to what we provide to any advertiser or campaign who asks for it.

Sen. Maria Cantwell: So, that was a yes? Is that a yes?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, can you repeat the specific question? I just want to make sure I get specifically what you're asking.

Sen. Maria Cantwell: During the 2016 campaign, Cambridge Analytica worked with the Trump campaign to refine tactics. Were Facebook employees involved in that?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, I don't know that our employees were involved with Cambridge Analytica, although I know that we did help out the Trump campaign overall in sales support in the same way that we do with other campaigns.

Sen. Maria Cantwell: So they may have been involved in all working together during that time period? Maybe that's something your investigation will find out.

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, I can certainly have my team get back to you on any specifics there that I don't know sitting here today.

Sen. Maria Cantwell: Have you heard of Total Information Awareness? Do you know I'm talking about?

Mark Zuckerberg: No, I do not.

Sen. Maria Cantwell: OK. Total Information Awareness was 2003. John Ashcroft and others trying to do similar things to what I think is behind all of this. Geopolitical forces trying to get data and information to influence a process. So when I look at Palantir and what they're doing and I look at WhatsApp, which is another acquisition, and I look at where you are from the 2011 consent decree and where you are today, I'm thinking is this guy outfoxing the foxes or is he going along with what is a major trend in an information age to try to harvest information for political forces? And so my question to you is, do you see that those applications — that those companies — Palantir and even WhatsApp are going to fall into the same situation that you've just fallen into over the last several years?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, I'm not— I'm not sure, specifically. Overall, I do think that these issues around information access are challenging. To the specifics about those apps I'm not really that familiar with what Palantir does. WhatsApp collects very little information and I think it is less likely to have the kind of issues because of the way that the service is architected. But certainly I think that these are broad issues across the tech industry.

Sen. Maria Cantwell: Well, I guess given the track record of where Facebook is and why you're here today, I guess people would say that they didn't act boldly enough. And the fact that people like John Bolton basically was an investor and a New York Times article earlier — I guess it was actually last month — that the BoltonPAC was obsessed with how America was becoming limp-wristed and spineless and it wanted research and messaging for national security issues. So the fact that, you know, there are a lot of people who are interested in this larger effort. And what I think my constituents want to know is, was this discussed at your board meetings? And what are the applications and interests that are being discussed without putting real teeth into this? We don't want to come back to this situation again. I believe you have all the talent. My question is whether you have all the will to help us solve this problem.

Mark Zuckerberg: Yes, Senator. So data privacy and foreign interference in elections are certainly topics that we have discussed at the board meeting. These are some of the biggest issues that the company has faced and we feel a huge responsibility to get these right.

Sen. Maria Cantwell: Do you believe the European regulations should be applied here in the U.S.?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, I think everyone in the world deserves good privacy protection. And regardless of whether we implement the exact same regulation, I would guess that it would be somewhat different because we have somewhat different sensibilities in the U.S. as to other countries, we're committed to rolling out the controls, and the affirmative consent, and the special controls around sensitive types of technology like face recognition that are required in GDPR — we're doing that around the world. So I think it's certainly worth discussing whether we should have something similar in the U.S., but what I would like to say today is that we're going to go forward and implement that regardless of what the regulatory outcome is.

Sen. Chuck Grassley: Senator Wicker. Senator Thune will chair next. Senator Wicker.

Sen. Roger Wicker: Thank you, Mr. Chairman and Mr. Zuckerberg, thank you for being with us. My question is going to be sort of a follow up on what Senator Hatch was talking about. And let me agree with basically his advice that we don't want to overregulate to the point where we're stifling innovation and investment. I understand with regard to suggested rules or suggested legislation, there are at least two schools of thought out there. One would be the ISPs, the internet service providers, who are advocating for privacy protections for consumers that apply to all online entities equally across the entire internet ecosystem. Now, Facebook is an edge provider, on the other hand. It's my understanding that many edge providers, such as Facebook, may not support that effort because edge providers have different business models than the ISPs and should not be considered like services. So, do you think we need consistent privacy protections for consumers across the entire internet ecosystem that are based on the type of consumer information being collected, used, or shared regardless of the entity doing the collecting, or using, or sharing?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, this is an important question. I would differentiate between ISPs, which I consider to be the pipes of the internet, and the platforms like Facebook, or Google, or Twitter, or YouTube that are the apps or platforms on top of that. I think in general the expectations that people have of the pipes are somewhat different from the platforms. So there might be areas where there needs to be more regulation in one and less than the other, but I think there are going to be other places where there needs to be more regulation of the other type. Specifically though on the pipes one of the important issues that I think we face and have debated is ...

Sen. Roger Wicker: When you when you say pipes you mean ISPs?

Mark Zuckerberg: ISPs, yeah. And I know net neutrality has been a hotly debated topic, and one of the reasons why I have been out there saying that I think that that should be the case is because, you know, I look at my own story of when I was getting started building Facebook at Harvard. You know, I only had one option for an ISP to use and if I had to pay extra in order to make it so that my app could potentially be seen or used by other people, then then we probably would be here today.

Sen. Roger Wicker: OK, well, but we're talking about privacy concerns and let me just say we'll have to follow up on this, but I think you and I agree this is going to be one of the major items of debate if we have to go forward and do this from a governmental standpoint. Let me just move on to another couple of items. Is it true that, as was recently publicized, that Facebook collects the call and text histories of its users that use Android phones?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, we have an app called Messenger for sending messages to your Facebook friends. And that app offers people an option to sync their text messages into the messaging app and to make it so that you can have one app where it has both your texts and your Facebook messages in one place. We also allow people the option ...

Sen. Roger Wicker: You can opt in or out of that?

Mark Zuckerberg: Yes it is opt in. It is opt in. You have to affirmatively say that you want to sync that information before we get access.

Sen. Roger Wicker: Unless you opt in, you don't collect that call and text history.

Mark Zuckerberg: That is correct.

Sen. Roger Wicker: And is that true for — is this practice done at all with minors or do you make an exception there for persons aged 13 to 17?

Mark Zuckerberg: I do not know, we can follow up.

Sen. Roger Wicker: OK, do that. Let's do that. One other thing. There have been reports that Facebook can track users' internet browsing activity even after that user has logged off of the Facebook platform. Can you confirm whether or not this is true?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, I want to make sure I get this accurate, so it would probably be better to have my team follow up afterwards.

Sen. Roger Wicker: You don't know?

Mark Zuckerberg: I know that the people use cookies on the internet and you can probably correlate activity between sessions. We do that for a number of reasons, including security and including measuring ads to make sure that the experiences are the most effective, which, of course, people can opt out of. But I want to make sure that I'm precise in my answer ...

Sen. Roger Wicker: Well, when you get back to me, sir, would you also let us know how Facebook discloses to its users that engaging in this type of tracking gives us that result?

Mark Zuckerberg: Yes.

Sen. Roger Wicker: And thank you very much.

Sen. John Thune: Thank you, Senator Wicker. Senator Leahy is up next.

Sen. Patrick Leahy: Thank you. Mr. Zuckerberg, I assume Facebook's been served subpoenas from the special counsel [inaudible] office, is that correct?

Mark Zuckerberg: Yes.

Sen. Patrick Leahy: Have you or anyone in Facebook been interviewed by the special counsel's office?

Mark Zuckerberg: Yes.

Sen. Patrick Leahy: Have you been interviewed?

Mark Zuckerberg: I have not.

Sen. Patrick Leahy: Others have?

Mark Zuckerberg: I believe so and I want to be careful here, because that — our work with the special counsel is confidential and I want to make sure that in an open session I'm not revealing something confidential.

Sen. Patrick Leahy: I understand. I just want to make clear that you have been contacted and you have had subpoenas.

Mark Zuckerberg: Actually, let me clarify that: I actually am not aware of a subpoena. I believe that there may be, but I know we're working with them.

Sen. Patrick Leahy: Thank you. Six months ago your general counsel promised us that you were taking steps to prevent Facebook for serving, what I would call, an unwitting coconspirator in Russia interference. But these unverified divisive pages are on Facebook today. They look a lot like the anonymous groups that Russian agent used to spread propaganda during the 2016 election. Are you able to confirm whether they're Russian-created groups, yes or no?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, are you asking about those specifically?

Sen. Patrick Leahy: Yes.

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, last week we actually announced a major change to our ads and pages policies that we will be verifying the identity of every single advertiser ...

Sen. Patrick Leahy: I asked about these specific ones — do you know whether they are?

Mark Zuckerberg: I am not familiar with those pieces of content specifically.

Sen. Patrick Leahy: But if you decided this policy a week ago, you'd be able to verify them?

Mark Zuckerberg: We are working on that now. What we're doing is we're going to verify the identity of any advertiser who is running a political- or issue-related ad. This is basically what the Honest Ads Act is proposing and we're following that. And we're also going to do that for pages.

Sen. Patrick Leahy: But you can't answer on these?

Mark Zuckerberg: I'm not familiar with those specifics cases.

Sen. Patrick Leahy: Well, you find out the answer and get back to me.

Mark Zuckerberg: I'll have my team get back to you. I do think it's worth adding, though, that we're going to do the same verification of the identity and location of admins who are running large pages. So that way even if they aren't going to be buying ads in our system, that will make it significantly harder for Russian interference efforts or other inauthentic efforts to try to spread misinformation through the network.

Sen. Patrick Leahy: Insofar that it's been going on for some time, some might say it's about time. You know, six months ago I asked you general counsel about Facebook's role as a breeding ground for hate speech against Rohingya refugees. Recently U.N. investigators blamed Facebook for playing a role in citing possible genocide in Myanmar. And there has been genocide there. You say you use AI to find this. This is the type of content I'm referring to — it calls for the death of a Muslim journalist. That threat went straight through your detection systems, it spread very quickly, and then it took attempt, after attempt, after attempt, and the involvement of civil society groups to get you to remove it. Why couldn't it be removed within 24 hours?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, what's happening in Myanmar is a terrible tragedy and we need to do more.

Sen. Patrick Leahy: We all agree with that.

Mark Zuckerberg: OK.

Sen. Patrick Leahy: But U.N. investigators have blamed you, blamed Facebook, for playing a role in the genocide. We all agree it's terrible. How can you dedicate — and will you dedicate — resources to make sure such hate speech is taken down within 24 hours?

Mark Zuckerberg: Yes, we're working on this. And there are three specific things that we're doing. One is we're hiring dozens of more Burmese language content reviewers because hate speech is very language specific. It's hard to do it without people who speak the local language. And we need to ramp up our effort there dramatically. Second is we're working with civil society in Myanmar to identify specific hate figures so we can take down their accounts rather than specific pieces of content. And third is we're standing up a product team to do specific product changes in Myanmar and other countries that may have similar issues in the future to prevent this from happening.

Sen. Patrick Leahy: Senator Cruz and I sent a letter to Apple. Asking what they're going to do about Chinese censorship. My question, and I'll place it for the record, I want to know what you will do about Chinese censorship when they come to you.

Sen. John Thune: Senator Graham is up next.

Sen. Lindsey Graham: Thank you. Are you familiar with Andrew Bosworth?

Mark Zuckerberg: Yes, Senator, I am.

Sen. Lindsey Graham: He said, "So we connect more people. Maybe someone dies in a terrorist attack coordinated on our tools. The ugly truth is that we believe in connecting people so deeply that anything that allows us to connect more people more often is de facto good." Do you agree with that?

Mark Zuckerberg: No, Senator, I do not. And as context, Boz wrote that — Boz is what we call him internally — he wrote that as an internal note. We had a lot of discussion internally, I disagreed with it at the time that he wrote it. If you looked at the comments on the internal discussion, the vast majority of people internally did, too.

Sen. Lindsey Graham: Would you say that you did a poor job as a CO communicating your displeasure with such thoughts. Because if he had understood where you were at, he would have never said it to begin with.

Mark Zuckerberg: Well, Senator, we try to run our company in a way where people can express different opinions internally.

Sen. Lindsey Graham: Well this is an opinion that really disturbs me and if somebody worked for me that said this, I'd fire them. Who's your biggest competitor?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, we have a lot of competitors.

Sen. Lindsey Graham: Who's your biggest?

Mark Zuckerberg: I think the categories of ... do you want just one? I'm not sure I can give one. But can I give a bunch?

Sen. Lindsey Graham: Mhmm.

Mark Zuckerberg: So, there are three categories that I would focus on. One are the other tech platforms so Google, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft we overlap with them in different ways.

Sen. Lindsey Graham: And they— do they provide the same service you provide?

Mark Zuckerberg: In different ways, different parts of—

Sen. Lindsey Graham: Let me put it this way, if I buy a Ford and it doesn't work well, and I don't like it, I can buy a Chevy. If I'm upset with Facebook, what's the equivalent product that I can go sign up for?

Mark Zuckerberg: Well there's the second category that I was going to talk about—

Sen. Lindsey Graham: I'm not talking about categories, I'm talking about, is there real competition you face, 'cause car companies face a lot of competition. If they make a defective car, it gets out in the world, people stop buying that car, they buy another one. Is there an alternative to Facebook in the private sector?

Mark Zuckerberg: Yes, Senator. The average American uses eight different apps that can communicate with their friends and stay in touch with people, ranging from texting apps, to e-mail, to—

Sen. Lindsey Graham: Which is the same service you provide?

Mark Zuckerberg: Well we provide a number of different services.

Sen. Lindsey Graham: Is Twitter the same as what you do?

Mark Zuckerberg: It overlaps with it, of course—

Sen. Lindsey Graham: You don't think you have a monopoly?

Mark Zuckerberg: It certainly doesn't feel like that to me.

(crowd laughs)

Sen. Lindsey Graham: OK. So it doesn't. So Instagram, you bought Instagram, why did you buy Instagram?

Mark Zuckerberg: Because they were very talented app developers who were making good use of our platform and understood our values.

Sen. Lindsey Graham: It was a good business decision. My point is that one way to regulate a company is through competition, through government regulation. Here's the question that all of us got to answer. What do we tell our constituents, given what's happened here, why we should let you self regulate? What would you tell people in South Carolina that, given all of the things we've just discovered here, is a good idea for us to rely upon you to regulate your own business practices?

Mark Zuckerberg: Well Senator, my position is not that there should be no regulation. I think the internet is increasingly—

Sen. Lindsey Graham: You embrace regulation?

Mark Zuckerberg: I think the real question, as the internet becomes more important in people's lives, is what is the right regulation not whether there should be or—

Sen. Lindsey Graham: But you as a company welcome regulation?

Mark Zuckerberg: I think if it's the right regulation, then yes.

Sen. Lindsey Graham: You think the Europeans have it right?

Mark Zuckerberg: I think that they get things right.

(crowd laughs)

Sen. Lindsey Graham: Have you ever submitted— (chuckles) That's true. So would you work with us in terms of what regulations you think are necessary in your industry?

Mark Zuckerberg: Absolutely.

Sen. Lindsey Graham: OK, would you submit to us some proposed regulations?

Mark Zuckerberg: Yes and I'll have my team follow up with you. So that way we can have this discussion across the different categories where I think that this discussion needs to happen.

Sen. Lindsey Graham: Look forward to it. When you sign up for Facebook, you sign up for Terms of Service, are you familiar with that?

Mark Zuckerberg: Yes.

Sen. Lindsey Graham: OK. It says, "The terms govern your use of Facebook and the products, features, apps, services, technologies, and software we offer (the Facebook Products or Products), except where we expressly state that separate terms (and not these) apply." I'm a lawyer and I have no idea what that means. But when you look at Terms of Service, this is what you get. Do you think the average consumer understands what they're signing up for?

Mark Zuckerberg: I don't think that the average person likely reads that whole document, but I think that there are different ways that we can communicate that and have a responsibility to do so.

Sen. Lindsey Graham: Do you agree with me that you'd better come up with different ways because this ain't workin'?

Mark Zuckerberg: Well, Senator, I think in certain areas that is true. And I think in other areas, like the core part of what we do. Right, if you think about just the most basic level, people come to Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, Messenger about a 100 billion times a day to share a piece of content or a message with a specific set of people and I think that that basic functionality people understand because we have the controls in line every time. And given the volume of the activity and the value that people tell us that they're getting from that, I think that that control in-line does seem to be working fairly well. Now we can always do better. And there are other— services are complex and there is more to it than just, you know, you go and you post a photo. So I agree that in many places we could do better, but I think for the core of the service it actually is quite clear.

Mark Zuckerberg: Thank you, Senator Graham. Senator Klobuchar.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar: Thank you, Mr. Chairman. Mr. Zuckerberg, I think we all agree that what happened here was bad. You acknowledge it was a breach of trust and the way I explain it to my constituents is that if someone breaks into my apartment with a crowbar and they take my stuff is just like if the manager gave them the keys or if they didn't have any locks on the doors, it's still a breach. It's still a break-in. And I believe we need to have laws and rules that are as sophisticated as the brilliant products that you've developed here. And we just haven't done that yet. And one of the areas that I've focused on is the election, and I appreciate the support that you and Facebook and now Twitter, actually, have given to the Honest Ads Act, a bill that you mention that I'm leading with Senator McCain and Senator Warner, and I just want to be clear as we work to pass this law so that we have the same rules in place to disclose political ads and issue ads as we do for TV and radio as well as disclaimers, that you're going to take early action as soon as June I heard before this election so that people can view these ads including issue ads. Is that correct?

Mark Zuckerberg: That is correct Senator. And I just want to take a moment before I go into this in more detail to thank you for your leadership on this. This I think is an important area for the whole industry to move on. The two specific things that we're doing are one is around transparency. So now you're going to be able to go and click on any advertiser or any page on Facebook and see all of the ads that they're running. So that actually brings advertising online on Facebook to an even higher standard than what you would have on TV or print media because there's nowhere where you can see all of the TV ads that someone is running, for example, whereas you will be able to see now on Facebook whether this campaign or third party is saying different messages to different types of people. I know that's a really important element of transparency. Then the other really important piece is around verifying every single advertiser who's going to be running political or issue ads.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar: I appreciate that. And Senator Warner and I have also called on Google and the other platforms to do the same. So memo to the rest of you, we have to get this done or we're going to have a patchwork of ads and I hope that you'll be working with us to pass this bill, is that right?

Mark Zuckerberg: We will.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar: OK. Thank you. Now on the subject of Cambridge Analytica, were these people, the 87 million people, users concentrated in certain states or are you able to figure out where they're from?

Mark Zuckerberg: I do not have that information with me. But we can follow up with your office.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar: OK. Because as we know, that election was close and it was only thousands of votes in certain states. You've also estimated that roughly 126 million people may have been shown content from a Facebook page associated with the Internet Research Agency. Have you determined whether any of those people were the same Facebook users whose data was shared with Cambridge Analytica? Are you able to make that determination?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, we're investigating that now. We believe that it is entirely possible that there will be a connection there.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar: OK, that seems like a big deal as we look back at that last election. Former Cambridge Analytica employee Christopher Wiley has said that the data that it improperly obtained — that Cambridge Analytica improperly obtained from Facebook users — could be stored in Russia. Do you agree that that's a possibility?

Mark Zuckerberg: Sorry, are you asking if Cambridge Analytica's data could be stored in Russia?

Sen. Amy Klobuchar: That's what he said this weekend on a Sunday show.

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, I don't have any specific knowledge that would suggest that, but one of the steps that we need to take now is go do a full audit of all of Cambridge Analytica systems to understand what they're doing, whether they still have any data, to make sure they remove all the data, if they don't we're going to take legal action against them to do so. That audit we have temporarily ceded that in order to let the U.K. government complete their government investigation first, because of course a government investigation takes precedence over a company doing that. But we are committed to completing this full audit and getting to the bottom of what's going on here. So that way we can have more answers to this.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar: OK, you earlier stated publicly and here that you would support some privacy rules so that everyone's playing by the same rules here. And you also said here that you should have notified customers earlier. Would you support a rule that would require you to notify your users of a breach within 72 hours?

Mark Zuckerberg: Senator, that makes sense to me and I think we should have our team follow up with yours to discuss the details around that more.

Sen. Amy Klobuchar: Thank you, I just think part of this was when people don't even know that their data has been breached, that's a huge problem and I also think we get to solutions faster when we get that information out there. I thank you and we look forward to passing this bill. We'd love to pass it before the election on the Honest Ads and I'm looking forward to better disclosure this election. Thank you.

Check back on this page — we're updating it live with the hearing.

Mikah Sargent is Senior Editor at Mobile Nations. When he's not bothering his chihuahuas, Mikah spends entirely too much time and money on HomeKit products. You can follow him on Twitter at @mikahsargent if you're so inclined.