How Apple fixed the MacBook Pro

There's this story about Steve Jobs coming into the Mac product meeting, dropping an iPad on the table, and asking them, in typical Steve Jobs fashion, why the Mac couldn't do that. Couldn't be that. Instant-on. With a battery that lasted the whole working day.

Thanks to the halo of the iPod and iPhone and iPad, Apple had gone from a beloved, if niche, computer company to a mainstream technology powerhouse. Sales of iOS devices were dwarfing anything they'd ever seen with macOS devices. And higher levels of computing were becoming approachable and accessible to more people than ever before.

The same desires and drives that led to the creation of the iPad led to the evolution of a whole new generation of Macs. It started with the 2011 MacBook Air, an ultra-portable that became ultra-popular. So much so, it went on to define a generation of knock-off ultrabooks.

What could a MacBook Pro do that was less about traditional power users and more about empowering the much larger mainstream prosumer market? Or, you know, if you're cynical, you could call that the desire to sell pro machines at pro prices to far more people. I

But the pro-market was changing as well. Sure, you still had your ultra-high-end pros who worked on cutting if not bleeding edge video, audio, photography, animation, science, and other areas where they constantly needed to render, and bounce, and export, and model, and compute more and faster than ever.

And thanks to software like Final Cut Pro X and Logic X and Lightroom and Xcode and Coda, gear costs coming down and processing power coming up, you also had people starting new companies and side hustles who also wanted pro machines. Realistically, sure. But even aspirationally. Even if only to keep 20 damn Chrome tabs open without freezing up their machine.

Those are the conditions, the ingredients, that I believe led to the 2016 MacBook Pro. To see if Apple could do with the Pro what they'd done with the Air, never mind what they'd done with the iPad.

Master your iPhone in minutes

iMore offers spot-on advice and guidance from our team of experts, with decades of Apple device experience to lean on. Learn more with iMore!

You can even see it in the first release line-up. There was a stripped-down model at the bottom that Apple expressly said was for those who wanted a Retina MacBook Air. But there was no loaded-up model at the top for people who wanted a more classical, more powerful, MacBook Pro. So much so, the whole line was sarcastically referred to as the MacBook Air Pro.

In a way, the strategy worked though. It totally worked. The 2016 MacBook Pro and its iterations reportedly sold better than any MacBook Pro before it. A whole new generation of pros bought into them. Hard.

I'll admit, I'm one of them. I legit loved everything about that generation of pros, except for the anemic webcam and, of course, the keyboard issues that gained so much attention later.

But traditional, high-end pros felt abandoned. Forgotten. Maybe even a little betrayed.

And, that's just part of the story.

I'm Rene Ritchie and this… is vector.

The memory

I'll get to the keyboards in a scalding hot minute. I swear. It's what everyone wants to hear about, I know. But I'm going to quickly cover a couple of other things first. Starting with the memory.

For the first couple of years, the then-new MacBooks Pro were limited to 16 GM of RAM. That's because they used LPDDR3 — or low power DDR 3 — memory. And, because Intel was behind schedule and getting behind-er, LPDDR4, which supported higher memory limits, just hadn't rolled out yet.

Back then, Apple wasn't willing to sacrifice on power efficiency, which meant battery life, so they stuck with the 16 GB limit and used custom storage controllers and ultra-fast SSD to try and make the swap so fast, most people wouldn't really hit the limit.

And… aside from just hating the number on the spec sheet, most people didn't. But, of course, high-end pros did.

So, by 2018, Apple reversed course. They went back to non-low-power DDR4 memory, added an option for 32 GB, and also added extra power cells so the overall battery life wouldn't change. And the 16-inch now goes to 64 GB

They also started increasing the storage options, going all the way up to 4 TB of SSD last year, and a whopping 8TB this year.

The ports

With the 2016 MacBook Pro, Apple also went all-in on USB-C and Thunderbolt 3. Two ports at the low end, four ports at the high end. Gone were the USB-A and HDMI ports, the SD card slot, and MagSafe. And, if you wanted them back, or you wanted anything else, you had to use adapters.

Now, some people decried that as being hostile to pros. But, paradoxically, it wasn't really. It was hostile to the very mainstream, prosumers Apple was targeting.

See, Pros are used to adapters. Firewire 400. Firewire 800. VGA. Display Port. HDMI. Mini Display Port. Thunderbolt 2. Compact Flash. CFast. And hubs, because there are just never enough ports regardless of what type they are.

It's the reality of working in production environments where equipment ranges from very old to very new. And there's tons of it.

You get used to them. You actually prefer them. You can throw away your old adapters as you get new gear and new cables, and take advantage of the new port's throughput. But you can't ever dig an old port out and shove in a better, newer one.

I mean, I just had to buy a new CFast reader for this camera here. So the beat goes on.

But the mainstream users, the people who just have tons of USB-A peripherals, including the Lightning to USB-A cables Apple kept shipping with iPhones until just this year — because they are so mainstream. The people who aren't using cinema cameras with their wacky storage formats, but the far more ubiquitous cameras that made SD card slots so convenient.

Apple was the company that dumped the floppy drive for USB-A to begin with and they certainly seem to believe USB-C would take off just as fast. And it hasn't. And, unlike almost everything else with the MacBook Pros, Apple hasn't reverted on this, not by a single port or slot.

Time has eased some of the pressure but not all of it, not yet. It's clear, though, Apple thinks it still will.

The thermals

The other big complaint about the 15-inch Macbook Pros, especially in the middle years, was thermal throttling. It's a complicated issue but one that's simpler to explain.

The 2016 MacBook Pro chassis was designed for Intel chips that would quickly shrink down to 10 nanometers, increasing power while balancing it with greater efficiency.

But Intel hasn't been able to come through and is now years and years behind schedule. Even when they did push out new versions of the old chips, they were chronically late in making the specific versions Apple needed available, and often couldn't even keep up with demand.

Redesigning the chassis would take time, and take people away from the iMac Pro, updating the Mac mini and MacBook Air, and getting the new Mac Pro out the door. So, Apple chose to manage the problem instead.

There was a bug in the 2018 version that made people think Apple had just failed to manage the thermals completely, but Apple apologized and it was fixed in a software update. Still, it became almost a cliche in so many videos and every comment section.

Now, Apple has opinions on this stuff that some would disagree with. They don't seem to mind running hot, even at thermal limits, like not at all. They also don't mind using faster chips that can't sustain peak performance because they firmly believe those chips still benefit burst-intensive workflows.

Cynics would say Apple needs to market 8-core, i9 machines just to keep up with the competition. Pragmatists, that Apple is making the best out of a bad silicon situation. Like, architecting everything, from Metal to the accelerators on the T2 chips and the GPUs to work not just with but around the processors.

Which is why people who just download and run benchmarks can't really see or understand what's hitting CPU, GPU, or accelerator blocks anymore, or how.

But for people who run and show real-world workflow tests, overall, the results have shown consistent year-over-year improvements.

Just not as big as anyone, including Apple, would have liked. Which is why the new 16-inch has a new thermal system to better address sustained load.

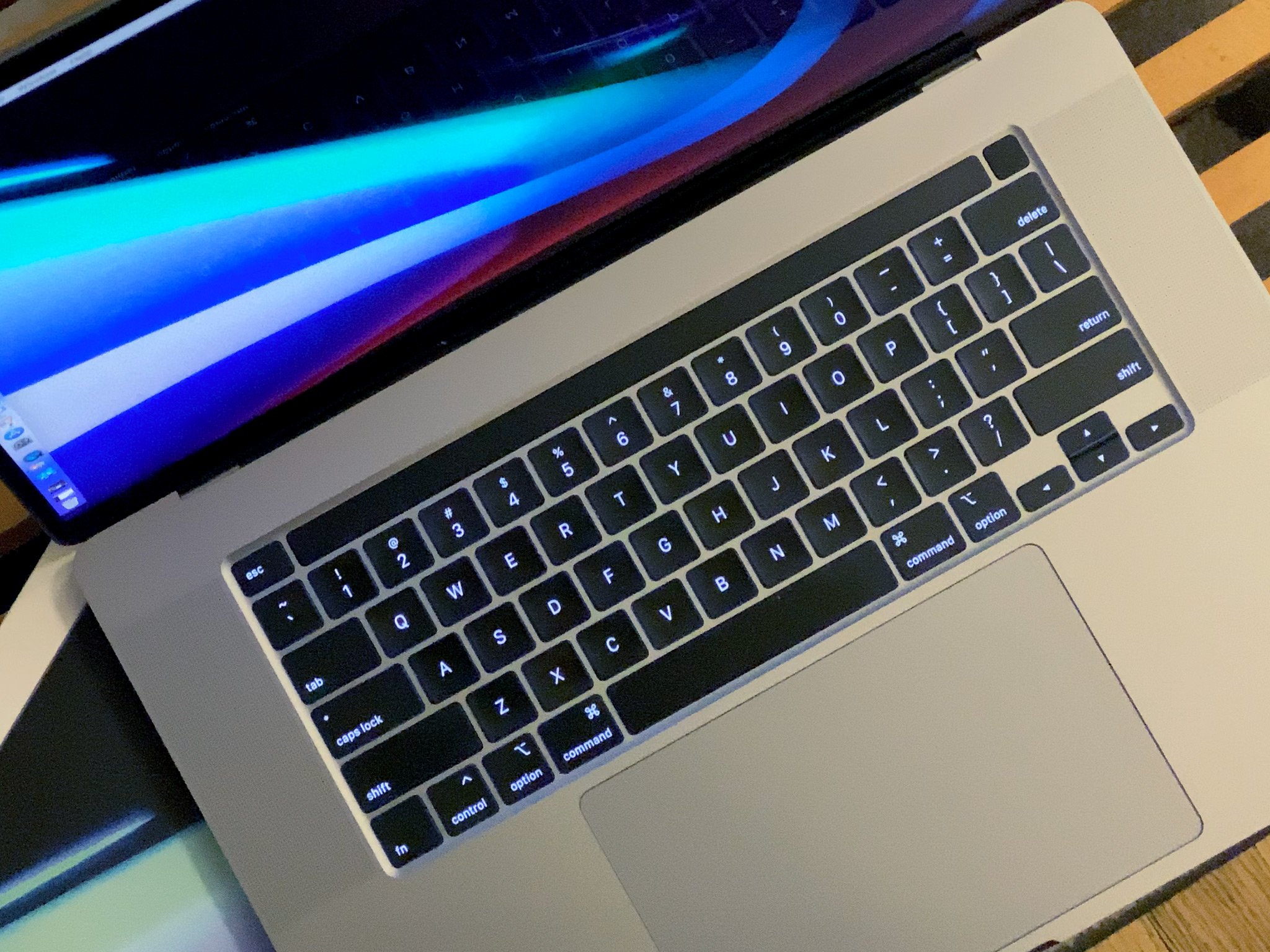

The Keyboard

When Apple launched the 12-inch MacBook Pro in 2015, it came with two huge changes to input. The first was the force touch trackpad. I know, I know, we'll get there, I swear. But this is important context for that. Apple had what were universally regarded as the best trackpads in the business already but it wasn't enough for them. They wanted to push the boundaries.

So, they got rid of the actual, mechanical trackpad switch and put a virtual one in its place. When the computer was off, it felt like a solid, dead piece of glass and metal. When the computer was on, that solid piece used proprioceptive trickery to come alive and make you think and feel an actual click where none still existed. Yeah, physics is a lie and fingers are liars.

It was a huge risk. People loved the MacBook Trackpad. But, Apple believed the changes were for the better. They would remove the hinge-like effect where the top of the trackpad barely clicked and the bottom clicked a lot, and make for a more consistent experience.

And… they were totally right. Going on five years later, while the force-press parts have never caught fire, the overall trackpad has been pure fire. It's now the better best trackpad in the business and, I daresay, people love it even more.

Apple also had what were universally regarded as some of the best keyboards in the business as well. But, again, it wasn't good enough for them. They wanted to push boundaries there as well.

The technology wasn't and isn't there for a dynamic, force touch keyboard, but Apple still wanted to solve some of the problems of the traditional scissor-switch keyboards. Like how loosey-goosey they felt.

So, they went with butterfly switches and metal domes that were four times as stable. They also made each key bigger and more concave.

Some people legitimately liked it better, myself included. Others, decidedly did not. Some that disliked it saw it as a fair compromise for a computer as ultra-portable as the 12-inch MacBook. Others, again, did not. Going on five years later, though, that keyboard hasn't caught fire. It's been on fire.

It's now commonly regarded as one of the worst keyboards in the industry, and while some people still like the feel better, others still hate its breathing guts, and everyone hates its failure rate.

And here's where Apple has its biggest problem — in the very beginning, right when Apple releases changes like the force touch trackpad and the butterfly keyboard, and people push back on them, hard, it's impossible to tell one from the other.

Humans hate change, so when there are immediate complaints, Apple just holds firm. They truly believe they made the right choices for the right reasons, and that as change-aversion fades, people will see what they saw, and they'll come to believe the choices were right, the reasons valid, and the benefits undeniable. It happens almost all the time.

So, before any widespread reports on failures as well, confident in the keyboard and their choices, and that anyone still change adverse would still come around, Apple went ahead and pushed the butterfly keyboard to the MacBook Pro.

But with some critical differences. First, even though the MacBook Pro was designed to be more portable to appeal to more portable pros, unlike the 12-inch MacBook, it wasn't designed to be ultra-portable. So, the segment of people who didn't like the butterfly switch as much as the scissor-switch but were willing to accept it on the MacBook just weren't willing to accept it on the MacBook Pro.

Also, the 12-inch MacBook still had a row of function keys, even if they were butterfly function keys. The MacBook Pro replaced that entire row with a Touch Bar.

One that, even though it took years to develop, was still delivered too early to include force touch like the trackpad. And one that took away the ESCape key, one of the most important keys to developers, who had become the single biggest segment of pros.

And that was a huge problem because. Apple is the only one who makes MacBook Pros.

If Microsoft makes an experimental Surface keyboard and some segment of the customer base hates it, those customers can just buy a Thinkpad or Dell or HP or whatever. With Apple, there's no one else to buy from.

While some, again, including me, preferred the new butterfly keyboards, others still hated them. And no one hated the old scissor-switch ones.

Then the stories about the failure rate started to hit.

First, the keys would get stuck, presumably from dust and debris getting in when they weren't supposed to and then being unable to get out.

Second, high usage keys would something either stop connecting and not enter a character when pressed, or bounce and enter double characters, which some theories attribute to wear or weakening of the metal dome.

Now, every component has a failure rate. I had a similar failure on an older, scissor-switch MacBook Pro and had to take it in for exactly the same repair. Bless AppleCare.

That's why it's never a specific failure but always the failure rate that's important. A certain amount of failure is normal. It sucks, but it's normal. As the rate gets higher, it becomes a bigger and bigger problem. As the perception of failure increases, well, that becomes another problem entirely.

When faced with these kinds of problems, there are a couple of different courses of action a company like Apple can take.

The first is to reverse course and go back or go different. Apple has done this in the past with things like the wide iPod nano and buttonless iPod shuffle.

The second is to hold course and try to make the new design work, especially if you as a company still believe it be better. Apple has done this before as well, like with the iPhone 4 antenna, which gave us the much better iPhone 4s antenna.

With the butterfly keyboards, Apple seems to have tried both. Likely because they still believe in the design and want to keep it around, especially for future ultra-portable MacBooks, but also to replace it with the new Magic Keyboard on the new 16-inch MacBook Pro.

And, in fact, the butterfly fixes we've seen have included a membrane to keep out dust and debris and a new material for the dome to preserve key connections.

The last set of fixed debuted earlier this year. The new keyboard just last week.

To be clear, neither has nothing to do with Jony Ive leaving.

Ritchie's law states any time someone says Steve Jobs would never, you can almost immediately find an example of Steve Jobs doing just that. I'm now officially extending that to include Jony Ive. But, more on that in another video.

Designing, prototyping, testing, iterating, testing, iterating, and releasing into production a new keyboard isn't something that happens in weeks and months. It happens in a year or two of months.

Which, if you factor in Apple's usual wait-and-they'll-come-around delay, the time between the keyboard launch in early 2015 and the first big report on failure rates in late 2017, to the debut of the new keyboard in late 2019 — which included wait time for Intel and AMD folded in, fits the timeline almost perfectly.

And, like I said in my hands-on and will say again in my review, the new Magic Keyboard so far feels so great. The stability of butterfly with the better travel and, hopefully, the resiliency of scissor switches and rubber domes.

It's so good, I think it would be a mistake for Apple to keep the butterfly keyboard around any longer, even on new, ultra-portable machines. And for the very reasons I mentioned just a few minutes ago.

Sometimes, like with the force touch trackpad, big gambles pay off. Others, like with the butterfly switch keyboards, they do not. Bury them. Salt the earth. Move on.

New, scissor-switch Magic keyboards for everyone.

The New Normal

Over the last couple of years, I think we've seen Apple do a real turn-around on the pro market. As much as 2016 and 2017 felt like pro machines were going way too mainstream and best, and being left to lie fallow at worst, 2018 and 2019 have been almost a renaissance.

Best of all, in my opinion, is that Apple has hired on a full-on Pro workflows team to hammer on new Macs, to complain and contribute, before they ever hit customers.

They've kept the more prosumer friendly models on the low end, which is fine. It fits with Apple's philosophy of always making technology approachable to more and more people.

But, they've been releasing better models on the high-end pro end now as well, including a new Mac mini and, soon, a new Mac Pro. I think Apple realized, as a company, they weren't really empowering if they left power users behind. And hopefully, this is now the new normal.

At least that's what I think. So, hit like if you do, share if you care, subscribe and Beskar steel that bell gizmo if you haven't already, and then jump into the comments and let me know — what do you think about how Apple is course-correcting on the new Macs? And what else do they still need to do?

Rene Ritchie is one of the most respected Apple analysts in the business, reaching a combined audience of over 40 million readers a month. His YouTube channel, Vector, has over 90 thousand subscribers and 14 million views and his podcasts, including Debug, have been downloaded over 20 million times. He also regularly co-hosts MacBreak Weekly for the TWiT network and co-hosted CES Live! and Talk Mobile. Based in Montreal, Rene is a former director of product marketing, web developer, and graphic designer. He's authored several books and appeared on numerous television and radio segments to discuss Apple and the technology industry. When not working, he likes to cook, grapple, and spend time with his friends and family.