Newton and the promise of paying for good software

Software is hard. It's one of those obvious statements that bears more scrutiny when investigated to its fullest; most people build software, be it for a computer, smartphone, tablet, or increasingly all of the above, with the intention of making money.

Increasingly, mobile apps rely on advertising as their primary form of revenue. This is a tried-and-true money generator after the perceived rejection of, but for certain gaming genres, paid-up-front apps. When CloudMagic debuted in 2013, CEO Rohit Nadhani told his team to offer the email client as a paid app because it built upon the gesture smarts of Apple's native Mail app and the search prowess of Gmail. Generous reviews and good word of mouth built its audience to some four million sign-ups and, at its height, 500,000 daily active users, but rising server costs and expensive R&D kept the company from making money.

After expanding to Android and dabbling on the desktop, CloudMagic rebranded as Newton two months ago, and shifted its business model from freemium — where Nadhani says the 4% of paid users were essentially subsidizing the entire company's user base — to a trial-and-pay alternative. Knowing there would be backlash, Nadhani, who moved his company from India to Silicon Valley to build its U.S. audience and benefit from Northern California's startup culture, hedged against it, penning a blog post that reads like an entreaty as much as a product update:

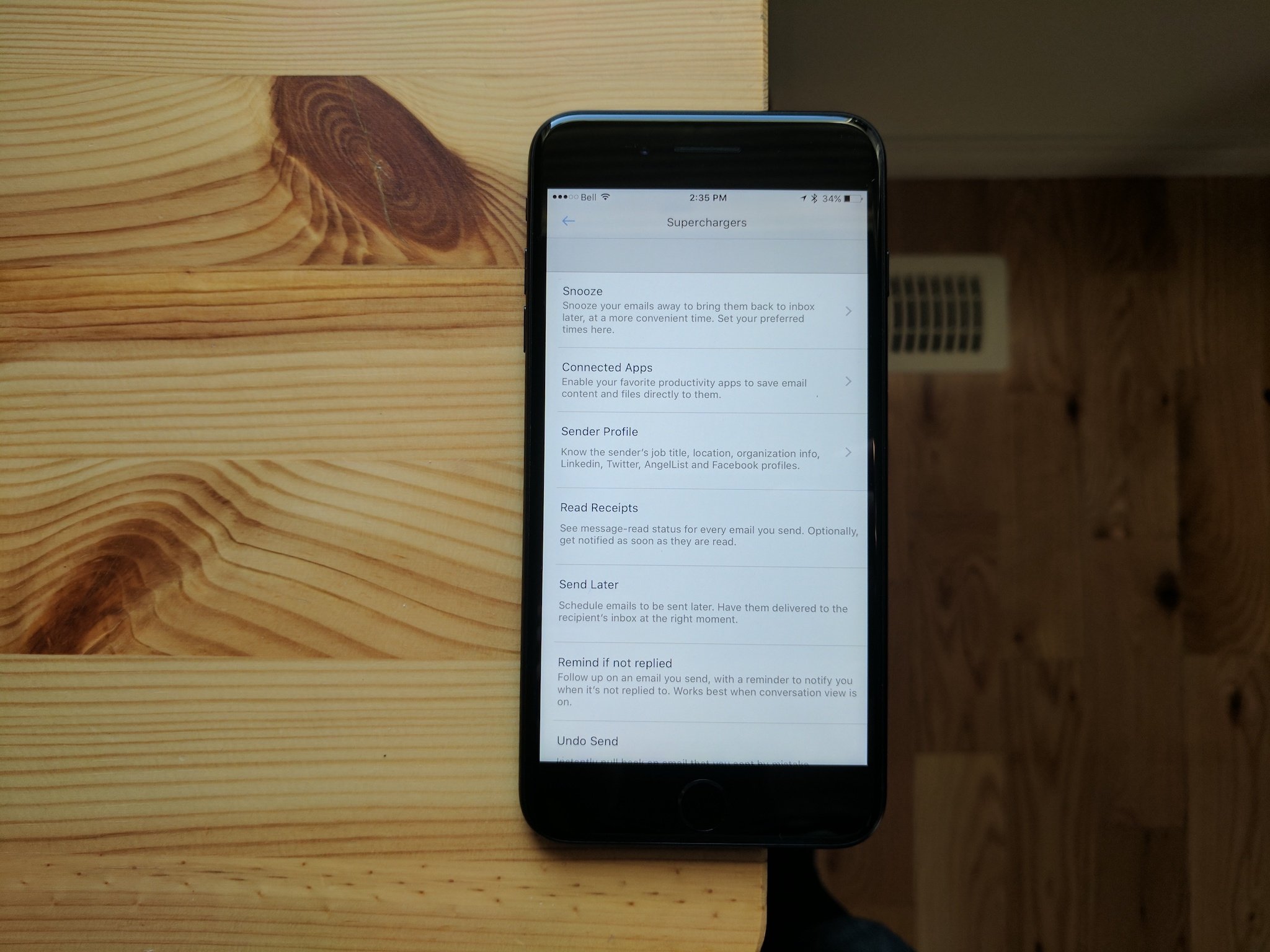

I'm excited to share with you that as of today, CloudMagic is graduating to be a more mature product and identity – Newton. Newton supercharges your email with power features like Read Receipts, Snooze, Send Later, Undo Send, Sender Profile, Connected Apps (previously Cards) and more, all with the trademark CloudMagic niceness and reliability.

The $49.99 annual price — half of a Dropbox subscription and about the same as Evernote Plus — is not particularly high for a premium email experience, but, as expected, the backlash was fierce. The iOS and Android apps dropped from the mid fours to under two stars on their respective stores, and people complained, both to Nadhani directly and over social media, that the cost did not reflect the value of the product.

This is despite a 14-day trial for Newton, which is available on iOS, Android and Mac, with a Windows client to come in the next few months, and an avid campaign to convince people that free email — even those not owned by Google — is full of compromise, including the sale of client information to third-parties. Nadhani refused to name names, but a bit of investigation revealed that one is the popular, and free, Mail by EasilyDo, which competes directly with Newton. CloudMagic stores some customer information, and downloads emails to expedite search, but that's about it, he says.

"I think people put too much emphasis on the collection of data," says Nadhani. "More important is that we don't sell your data," referring to Newton's privacy policy. But email is built on two of the oldest protocols, POP and IMAP, that companies have been building atop of for years. Many of the above "power features," like Read Receipts, Snooze, Send Later, and Undo Send — and the connection of Newton to many third-party APIs, from Evernote to Pocket to Asana, Todoist, OneNote, Trello and ZenDesk — require a powerful back end that Nadhani says is battle-tested and ready to scale.

Nadhani says he has turned down acquisition offers, opting to continue building the platform and adding to the growing technology stack.

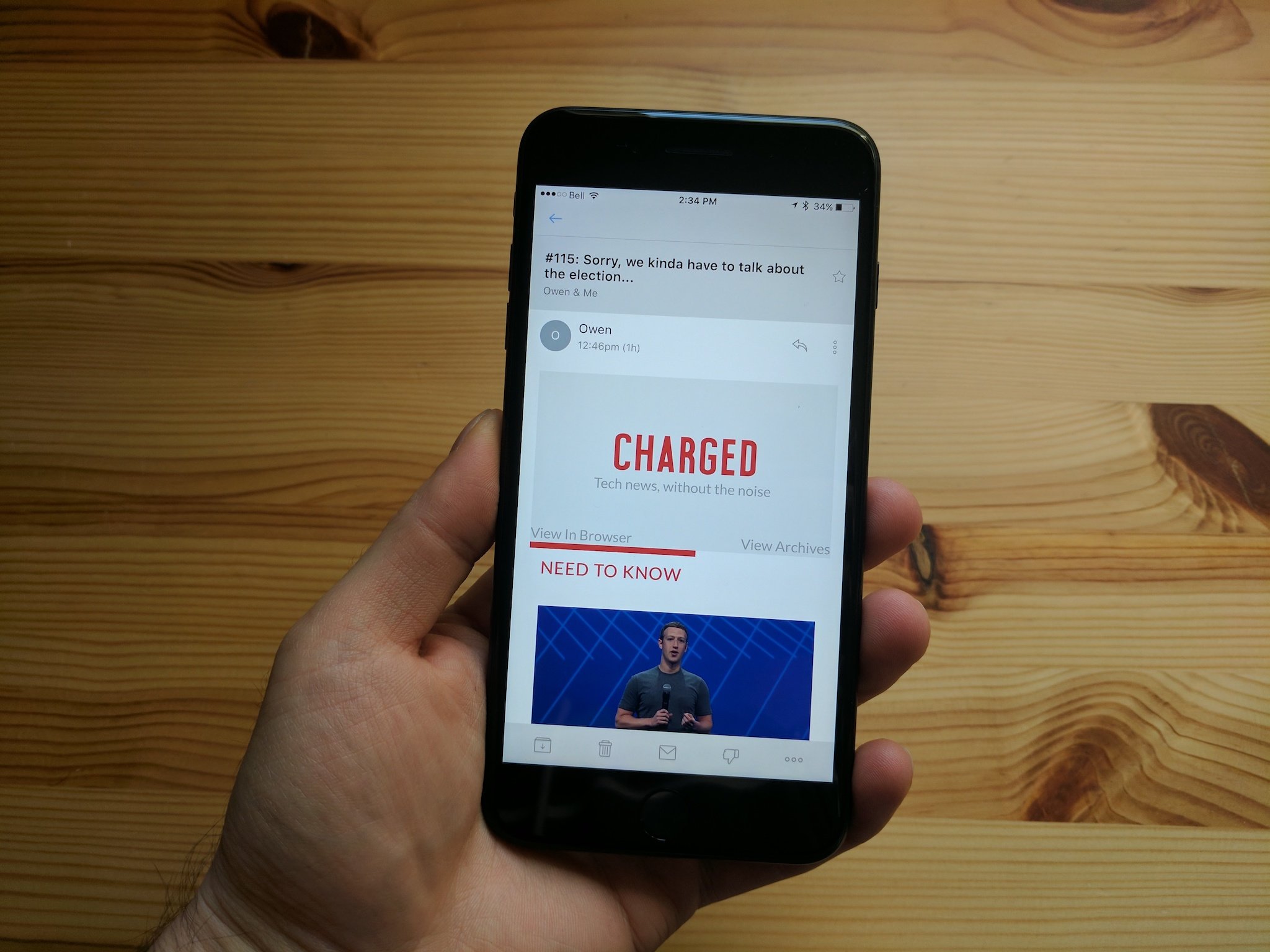

"Newton is meant for power email users," with the goal of providing a "consistent, similar experience across platforms." After trialling Newton for two weeks, I can say that there is method to the the company's madness: I have no desire to return to the ad-infested waters of the Gmail client, even if both of my main emails use are Google-based. On iOS, Newton is simple and fast — really fast — with the gestures and toggles I want that sync over the cloud. It's a seamless experience that I have yet to find as well implemented in any other email front-end, and it's nice to know that Newton, despite its smaller size, will live on.

Master your iPhone in minutes

iMore offers spot-on advice and guidance from our team of experts, with decades of Apple device experience to lean on. Learn more with iMore!

Nadhani says that he has turned down a number of acquisition offers, opting to continue building the platform and adding to the growing technology stack. "Cross-platform is a strategic advantage for us, as a lot of users have a combination of Windows [on the desktop or laptop] and iPhone in their pocket. That's a unique selling point. A lot of the code between iOS and Mac is shared, too, as they are built on Swift, and the sync engine is the best out there." He points to that server-dependent aspect of Newton as a huge advantage to the service over others, since it is how the biggest companies in the world, from Facebook to Amazon to Google, maintain their leadership in various categories.

"On the surface, Newton looks like an email client but all of the hard work is in the backend," says Nadhani. Unfortunately, it takes really spending time — perhaps longer than two weeks for complete newcomers to the platform — to see that upside, and the $49.99 annual fee may cause some people to balk. He says that the delta between his company's tech stack and the competition will only increase as his growing staff implements the beginnings of a machine learning strategy, though he won't expand on what that currently means.

"The reality is that we're going to around in three years directly because of the revenue we're collecting by users."

But he does expand on his feelings about high-value acquisitions like WhatsApp, which he says "skews peoples' perspectives" about the viability of business models. Newton is one in a sea of possible email clients to choose, but he says that many companies, like Dropbox acquisition target Mailbox, which shut down after failing to integrate into the company's product line, make the wrong decision to sell early, and end up disappearing. "People think we are dying because we're not looking to raise money or rely on manipulable metrics like DAUs, but the reality is that we're going to be around in three years directly because of the revenue we're collecting by users." It's a strategy that Evernote and Dropbox have had to learn the hard way, and smaller companies like Newton, neé CloudMagic, can avoid.

Staying small, humble and profitable seems, to Nadhani, to be the only way forward.

Daniel Bader is a Senior Editor at iMore, offering his Canadian analysis on Apple and its awesome products. In addition to writing and producing, Daniel regularly appears on Canadian networks CBC and CTV as a technology analyst.