The Switch to Intel

Rumors had been mounting that Apple was frustrated with the PowerPC chips it had been using. At the heart of the problem was the PowerBook, as Charles Moore points out:

In November 2003, David Russell, Apple's director of product marketing for portables and wireless, told Computerworld that Apple would someday like to offer a PowerBook G5. "We certainly want to do that," he said, "But it's going to be a while. We think the G4 has a very long life in the PowerBook." The main obstacle in getting a G5 processor into a portable was the need to keep the processor cool, Russell said. "Have you looked at the inside of the G5 tower?"

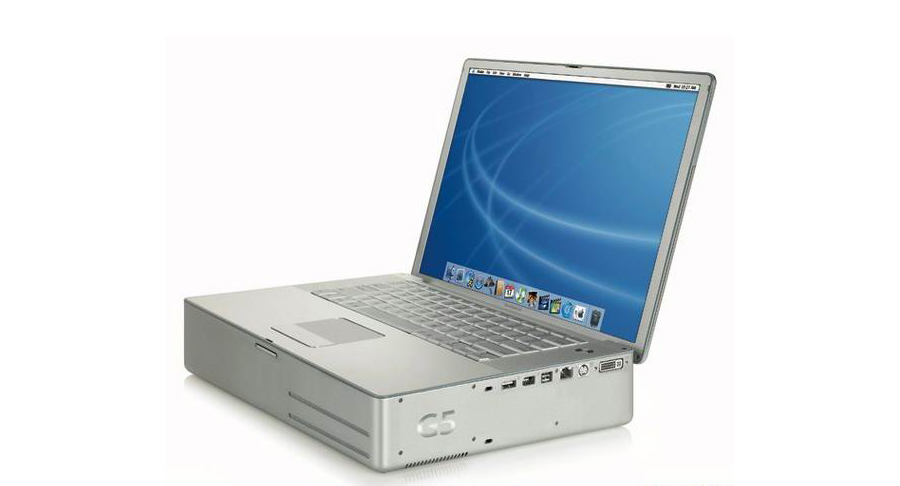

In fact, the PowerMac case was radically redesigned to accommodate the G5's massive thermal needs. The tower has numerous computer-controlled fans and four separate thermal zones to keep things cool and quiet. All of that engineering seemed impossible in a PowerBook, leading to this image floating around Mac forums at the time:

Yikes.

In his keynote address, Jobs addressed the challenges in front of Apple working with the PowerPC roadmap. Apple hadn't been able to deliver the 3.0 GHz Power Mac G5 the company had promised:

We can envision some great products we want to build for you, but we don't know how to build them with the future PowerPC roadmap.

(That's a pretty sick Steve Jobs burn.)

According to Jobs, this all came down to a metric he called "Performance Per Watt." In short, only Intel could give Apple the power they wanted in an efficient package. PPC was just too hot and too power-hungry for Apple to stay the course.

OS X's Secret Life

Jobs made a big reveal on stage to much laughter from the audience of developers and journalists:

Master your iPhone in minutes

iMore offers spot-on advice and guidance from our team of experts, with decades of Apple device experience to lean on. Learn more with iMore!

OS X has been leading a secret double life.

Turns out, since day one, Apple had put in place a safety net: OS X must be processor independent; every release of OS X had been compiled for PPC and Intel.

For those familiar with NeXTSTEP, this shouldn't have been a surprise. The OS had been running on Intel years before this announcement; Apple had just kept that project alive as NeXTSTEP evolved into OS X.

The Developer Transition

The Intel switch meant developers would need to recompile their applications to work on the new chipsets. Apple came to WWDC prepared for this. A new version of Xcode was capable of building "universal" binaries that would run natively on PowerPC and Intel machines.

While Jobs said many developers could get their apps ready with just a little work, for some bigger applications, this wasn't the case. For those developers and users, Apple shipped Rosetta, a translator that allowed Intel Macs to run PowerPC code at nearly full-speed.

Unlike Classic Mode, it was invisible. In everyday use, a user should never know if the application they were in was built for Intel or not. It had some limitations,#Compatibility) but more than held people over until things like Office and Photoshop made the jump.

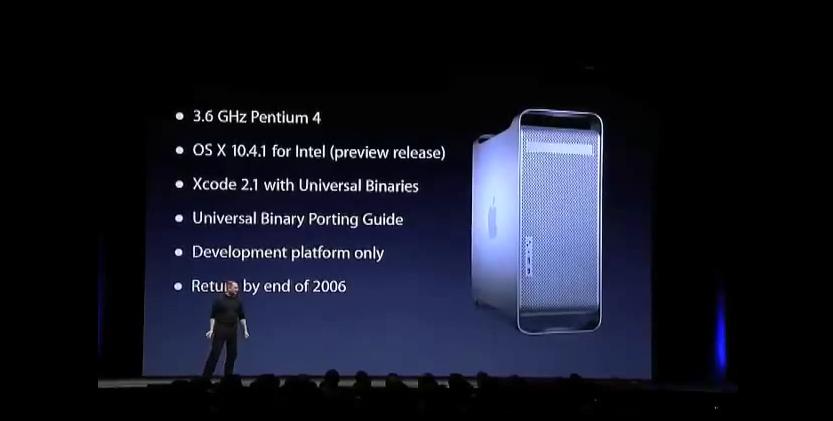

For developers who wanted or needed to work with Intel hardware early, Apple had a solution: the Intel Developer Transition Kit:

A stripped-down Intel Mac strapped to the inside of a PowerMac G5 case, these machines were $999 loaners that could be used by developers to fine tune their products. They had to be returned to Apple, as the reference hardware wasn't ever designed to be in the hands of normal users.

The Products

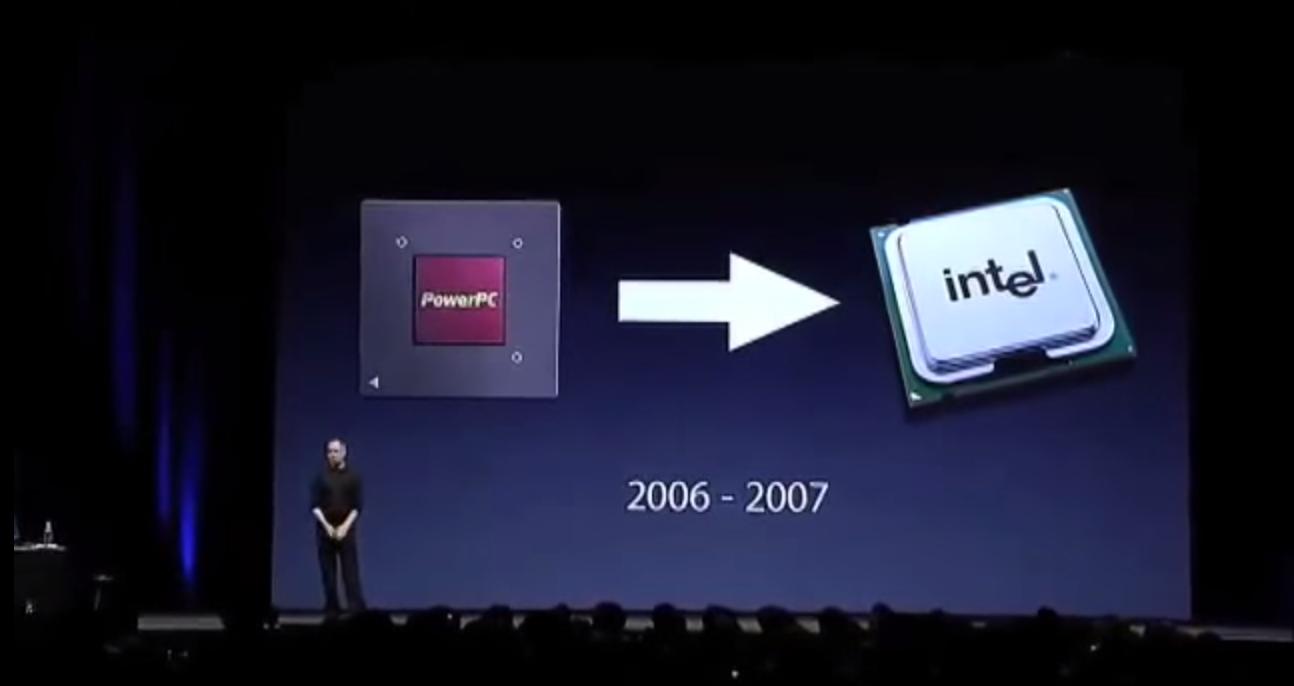

In 2005, Jobs said that this would be a two-year transition. Apple hoped to have the first Intel Macs shipping by WWDC 2006, with the entire line being moved over by the end of 2007.

Apple ended up moving much faster than that. The first Intel machines — the iMac and PowerBook MacBook Pro — were announced in January 2006.

The Mac mini followed in February, with the MacBook replacing the iBook in May. In August 2006, Apple announced the transition was complete with the new Xserve and Mac Pro. We've lived in an all-Intel Mac world for a decade.

Today, of course, PowerPC support is a thing of the past. 2011's Mac OS X Lion shipped without Rosetta support, and an iTunes update in 2012 made it the last Apple application to leave PowerPC behind.

The OS Is What Matters

When Apple announced this, part of the Mac community was up in arms. After years of mocking Intel chips in their advertising, Apple was now praising the company's technology. It was a bit much to swallow for some.

How could an Intel box feel like Mac? Would Intel's firmware, dubbed EFI, give users the freedom APple's old Open Firmware had? Without the ability to run the Classic environment, Intel Macs were a nonstarter for some users, regardless of personal feelings about the platform.

(I'm completely side-stepping this discussion. 2005 was a weird time.)

Jobs addressed this in his closing remarks:

The soul of the Mac is its operating system, and we're not standing still.

He was right. I was a big Mac user before the transition, and my first MacBook Pro felt like the PowerBook it replaced. The Mac was still the Mac, just faster and quieter.

The Future

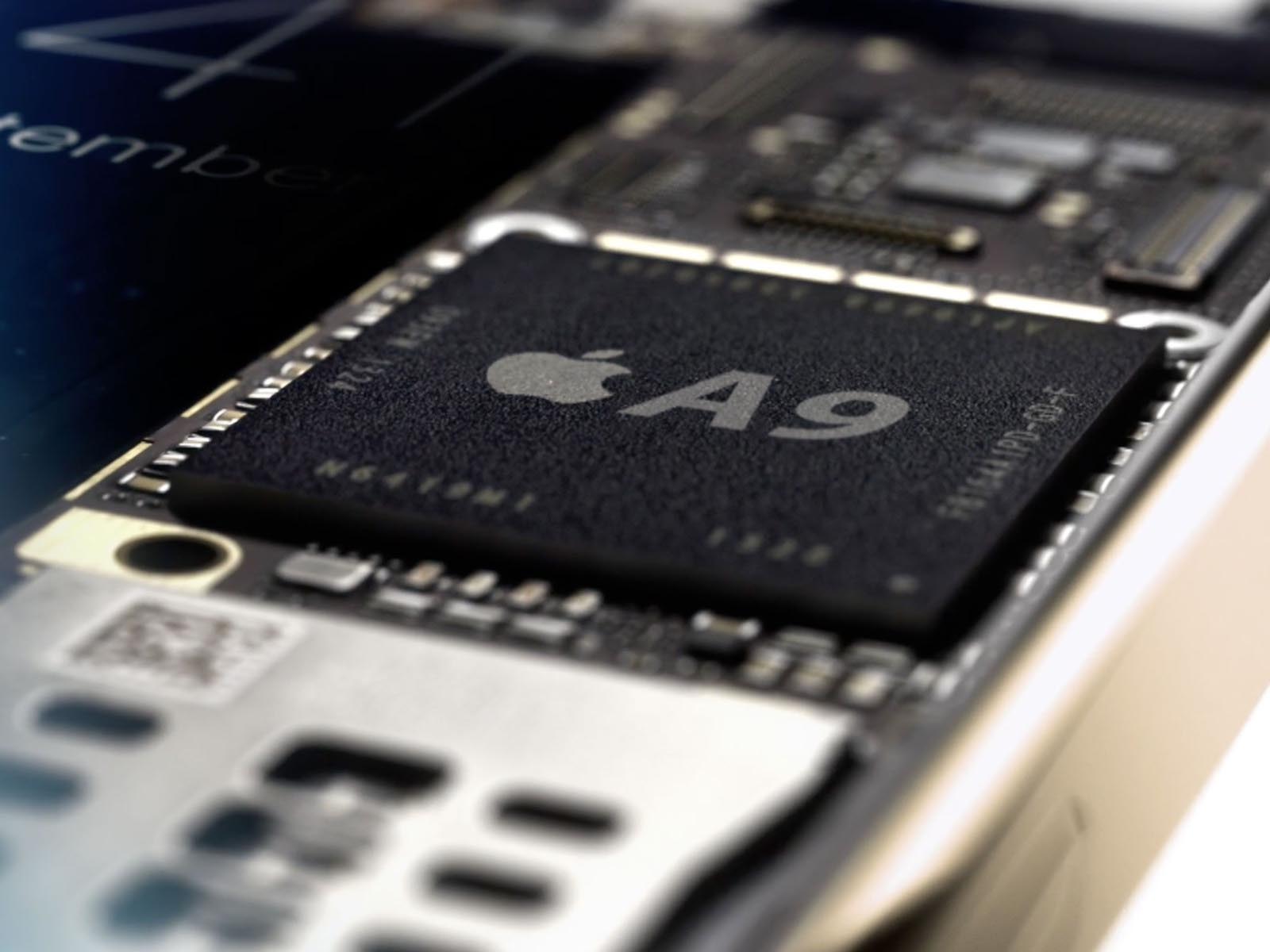

Historically, the Mac has seen several big transitions. In the mid 1990s, Apple moved from 68k processors to PowerPC chips. The early 2000s saw the transition away from the classic Mac OS to Mac OS X, and then the switch to Intel around 2006. It's been a long time, and while iOS devices are what are boosting the company's bottom line, the Mac is still important.

There's been a lot of talk about the pros and cons of Apple moving to ARM chips for the Mac. If that's going to happen, I still think it's several years off. While the 12-inch MacBook seems like a good candidate for an Apple-designed chipset, I don't think anything ARM-based can take on the i5 and i7 that Apple ships in most Macs, let alone the Xeon processors that power the Mac Pro.

If Apple does move away from Intel, it will leave things like easy virtualization of Windows behind. That's a big deal for a lot of users, but is it enough to stop the change? Time will tell.

No matter what happens, I think the Mac will always feel like home for those of us who love it.

Stephen Hackett is the co-founder of the Relay FM podcast network. He's written about Apple for seven years at 512 Pixels, and has more vintage Macs than family members living in his Memphis, TN home.